NID Tapes interview – “it’s a totally new branch of the tree of electronic music” | Juno Daily

Archive discovery re-opens world of sublime musicality

Released next month on The state51 Conspiracy, NID Tapes: Electronic Music in From India 1969-1972 is a throwback to the early days of analogue composition. The compilation escapes the usual tendency towards Eurocentrism in championing this field, showcasing the collective’s experiments with the Moog synthesizer, tape collage, vocal techniques and field recordings – creating a unique fusion of Western and Indian avant-garde traditions.

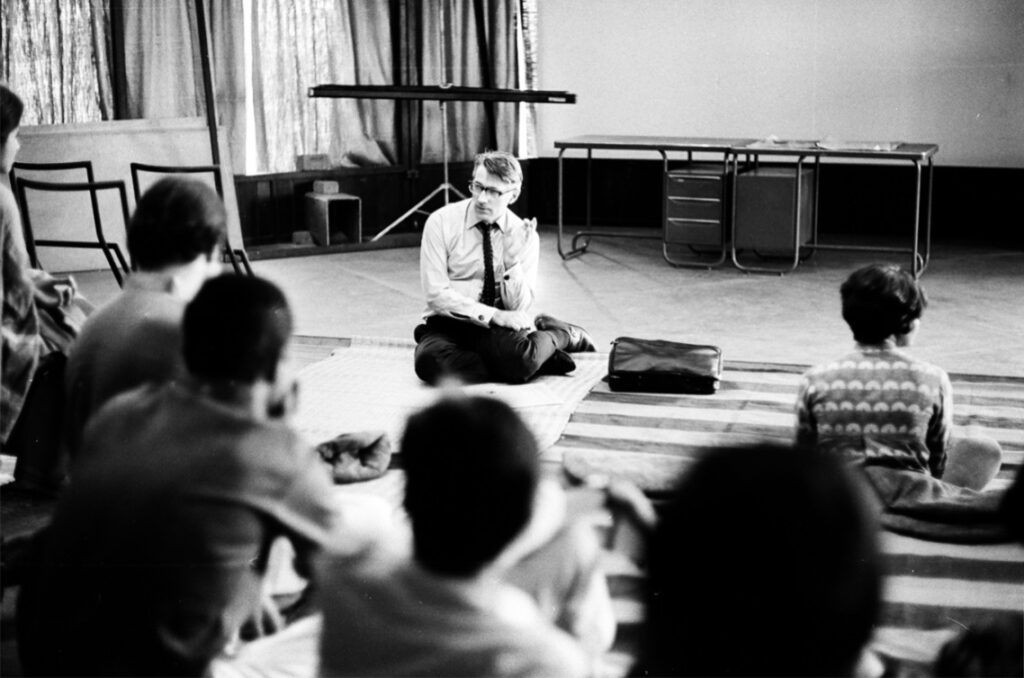

In 1961, India’s first Institute of Design was founded in Ahmedabad after the India Report was published, a post-independence commission by Charles and Ray Eames who spent three months in India making design recommendations for the government. The institute was a hub of radical experimentation headed by the Sarabhais – a prominent, philanthropic family who were acquainted with Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbousier, Montessori and Bauhaus, as well as being influenced by the educational ideals of Gandhi- that combined Western modernist thought with the holistic perspective and spiritual thought of India.

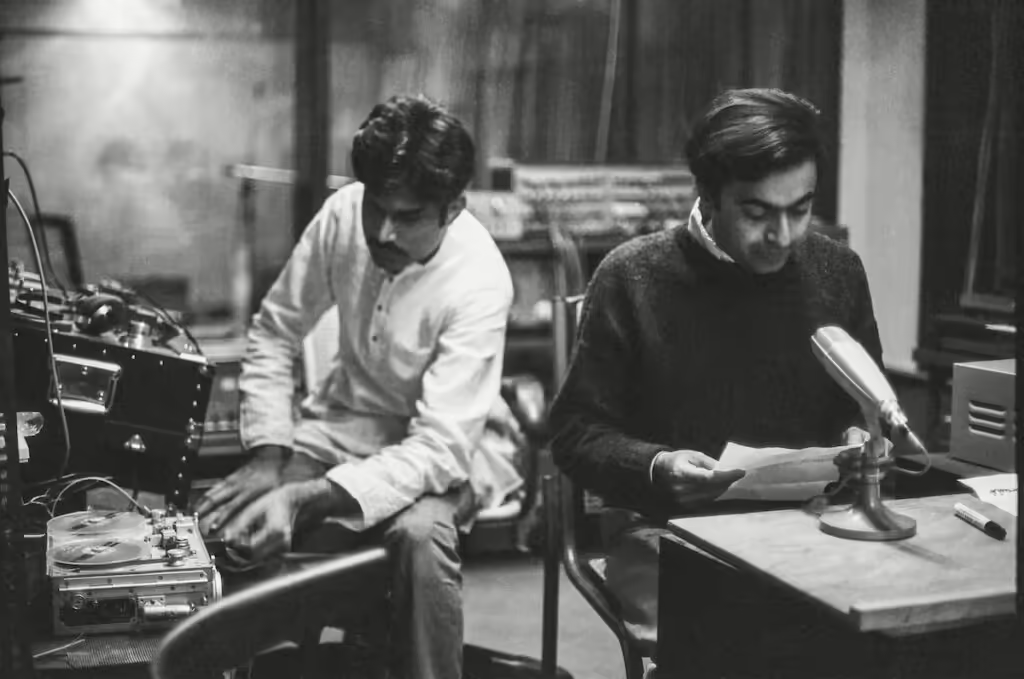

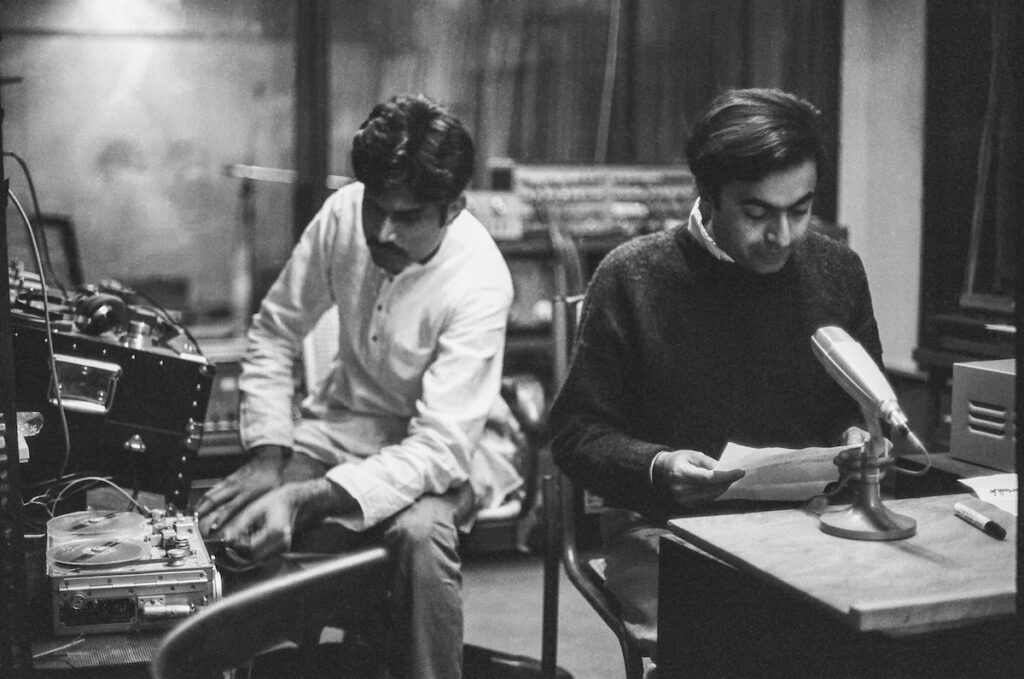

In 1969, The NID invited the experimental musician, David Tudor, to set up an electronic music studio and equipped it with a Moog Synthesiser. The sonic vision of the institute was guided by Gita Sarabhai, who had trained with John Cage in the US and acquainted him with Indian Classical Music, as she helped the studio amass a collection of tape machines, along with the synthesiser, and initiated structural and aesthetic experiments with sound.

During a trip to Ahmedabad, the London-based musician and artist, Paul Purgas, found a collection of tapes from the studio dating back to 1969. five years later, after a BBC Radio 3 documentary and an exhibition at this year’s CTM festival in Berlin, the tracks are being released as a compilation.

After finding the tapes, Paul Purgas could immediately see that they were of value and importance but he’d never worked with analogue tape before. After learning the foundations of conservation at the British Library, Purgas was finally able to listen to the tapes a year later. “When I got the chance to run the reels, it was an incredibly magical first glimpse into a set of recordings that hadn’t been played for decades. It was amazing to encounter the breadth of different approaches to sound and music production from that time,” he told me. The prescience of the material surprised Purgas, as far from being a collection of arcane sound recordings, the archive contained the essence of proto-techno, Krautrock and metal.

Collated as a 19-track album, The NID Tapes: Electronic Music from India 1969-1972 contains a range of different compositional styles, from electronic improvisations inspired by ancient Indian rhythmic Talas to futuristic synth innovation. The previously unknown tracks utilise analogue synthesis, tape collages, voice experiments and field recordings, showcasing the work of the revolutionary project and offering a special insight into a specific sonic imaginary of post-colonial India.

Purgas titles this sound-world ‘Indo-Futurism’, as like other strands of electronic music, the South Asian avant-garde was heavily inspired by science fiction and the golden era of space exploration. Regarding the NID specifically, Gita Sarrabhai’s brother had founded the ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation), further entrenching this established link and the forward-facing attitude of the Sarrabhai family.

Jinraj Joshipur is the only surviving artist on the compilation and this extra-terrestrial sound is most clearly heard on his composition, ‘Space Liner 2001 II’. After speaking to Joshipur, Purgas explains in Subcontinental Synthesis: Dreams & Lost Futures – an essay published by Strange Attractor Press as part of a book to accompany the release – that his production ‘took the form of an imagining of what it would be like to travel aboard an interstellar spacecraft, witnessing the universe passing by from a window.’

During the 1960s and 1970s other studios – such as the GRM in Paris, the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop and Cologne’s NWDR studio – were similarly enamoured by space and the sonic potential of electronic music. Purgas suggests that the NID tapes do bear some similarities to the work of these influential studios, but he’s also keen to impress that the tapes carry distinct properties that mark them out as being specifically derived from a South Asian context. Purgas goes on to explain this divergence, “either it’s the different approaches to processing traditional Indian instruments, whether that’s processing the Tanpura or Tabla through analogue effects…Or simultaneously, a desire to impose a very Indian musical set of traditions onto the Moog synthesiser,” Purgas likens this to the modality of Indian cinema, as a Western medium that came to India and was subsequently appropriated and remoulded into a new cultural form.

Available both digitally and as an LP, Paul thought it was important to make sure the record isn’t constrained to a vinyl-only audience. Creating the LP was a protracted process, as Paul enlisted the help of Shreya Aurora, a graduate from the Institute of Design, to give the record its unique aesthetic and etching on the 4th side. The impact of Covid-19, as well as floods in the region, also slowed down their progress. “I wanted to platform the Institute’s spirit of design production and that inevitably ended up causing lots of delays. But I wanted to present the music within the context that it was born out of.”

During the process of creating the compilation, Paul took 30 hours of audio and shaped it into a listening experience that resonates with contemporary audiences. “A part of that process has been thinking through areas of the archive that feel like they have the possibility of conveying the timelessness of electronic music. I wanted to focus on the points in the archive where I felt the sonics travelled well into the present, where they could transcend a historical sense of sound and feel like they were in a dialogue with contemporary music,” he explained.

For Paul, the archives represent a “totally new branch of the tree of electronic music and a non-Western modernism.” As an electronic musician from South Asian heritage himself, as part of the Bristol-based multidisciplinary duo Emptyset, Paul has often felt as if he’s drawing from American and European reference points as an outsider. After the discovery of the tapes, he felt he was walking the same footsteps that people from his culture had before for the first time. “This body of material brings a sense of belonging to a lot of electronic musicians from South Asians and the diaspora.”

Unlike the NID studio’s Western counterparts, it was never able to achieve the same lasting legacy. The structural conditions that paved the way for the studio dissipated, as geo-political tensions between India and the US intensified, India suffered economic hardship and the studio was never able to tie itself to the establishment of an Indian TV network, as the Radiophonic Workshop was able to do with the BBC. Questions remain over the longtime impact of the studio, as additional forgotten archives need to be unearthed to plot the history of South Asian electronic music.

Paul Purgas’ archiving and research into the NID studio is a vital intervention into the established history of experimental electronic music, raising questions around how the genre’s narrative should be told in the future. But for now, as Geeta Dayal writes in Subcontinental Synthesis, ‘it is a small miracle that the vintage Moog recordings from Ahmedabad exist, and that we can now listen to them. In the inspiring music, we hear bold new pathways for the future.’

Charlie Bird

Pre-order your copy of NID Tapes: Electronic Music in From India 1969-1972